‘Courts … are slow to embrace change,’ said a judge who considered (and refused) a proposal to extend legal rights to chimpanzees, but she also added, citing a different judge: ‘times can blind us to certain truths and later generations can see that laws once thought necessary and proper in fact serve only to oppress.’[1]

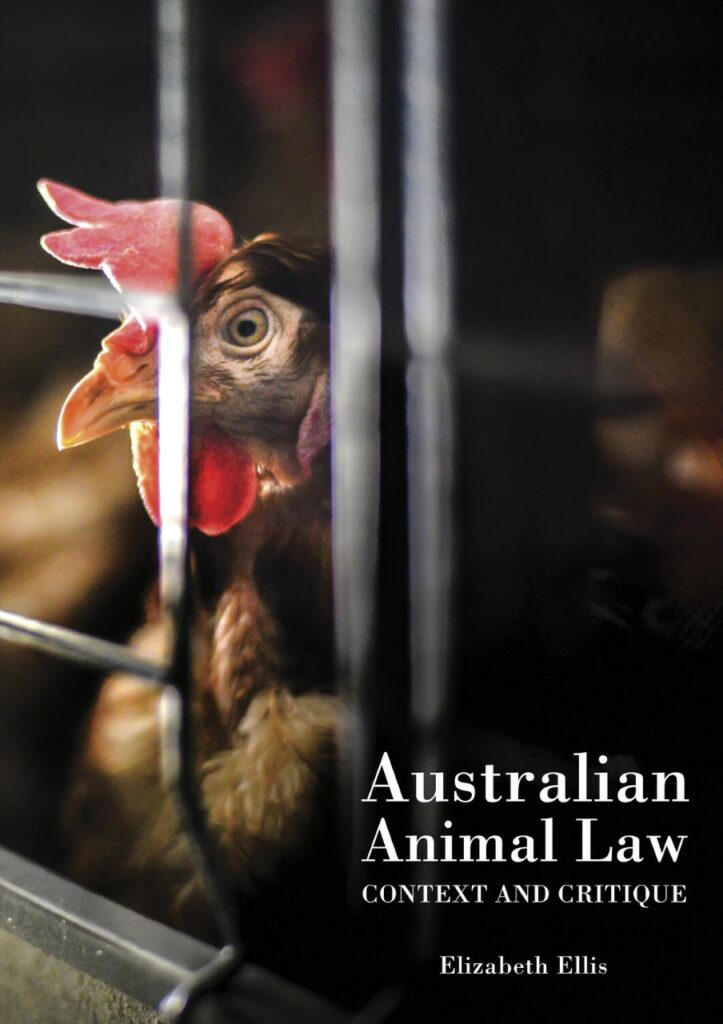

I was under no illusion about the severely disadvantaged legal status of nonhuman animals nationally and internationally. Despite my familiarity with the various practices and processes involved in animal-based industries, at different points Elizabeth Ellis’ new book Australian Animal Law (Sydney University Press 2022) left me gasping for air.

Elizabeth taught law at the University of Wollongong, published academic and other works on the topic, and in 2008 introduced animal law into the Bachelor of Laws degree – one of the first university courses in animal law in Australia. Her new book, which focuses on Australian law but also considers the global situation, is an important document and comes at a time when the divide between what consumers expect, based on their growing concern for animal wellbeing, and what they unwittingly support is perhaps more pronounced than ever before.

AASA: Most people believe, just like I did for a long time, that other animals enjoy a moderate level of protection – not just companion animals but others, too. Farm animals, for example: People have heard that there are some codes of practice to observe; even if they haven’t heard about the codes they automatically assume that they exist, that the industry dealing with sentient beings will be regulated somehow. However, what your analysis reveals is that in reality animals used for food, clothing and other commodities, are virtually without protection? As far as welfare is concerned, animal agriculture is not regulated, cruelty is systemic, what we see when an undercover video emerges and shocks the viewer, is usually not an aberration but constitutes standard practice?

EE: Codes of practice, and now standards and guidelines, regulate farmed animal welfare to some extent but the standard of protection is low and inconsistent with contemporary science as well as community expectations. As you say, we assume a certain level of legal protection for animals but we don’t actually see what the law permits, nor do we have ready access to information about enforcement. In reality, ‘animal welfare’ codes and standards allow considerable cruelty, for example painful procedures routinely performed on farmed animals without anaesthetic or pain relief although they would be criminal offences if done to a dog or cat. These codes and standards are then used as shields for industry, with the very limited protections rationalised in various ways. For example, it’s now routine to involve animal welfare stakeholders at some point in the development process and the resulting draft codes/standards are exposed to a public consultation process. This enables governments and industry to claim that the concerns of animal welfare organisations and the broader public have been taken into account but in practice they are more about legitimising industry preferences than genuine consultation. Evidence for this includes the fact that animal welfare organisations are always the minority stakeholders in the process and their recommendations, along with strongly expressed community views, are regularly ignored. Another rationalisation is that codes and standards are science-based but again the story is much more complicated. Part of the problem here is a narrow understanding of animal welfare and what constitutes cruelty, a problem reinforced by the lack of industry-independent research. Industry preferences, such as keeping animals closely confined, are commonly rationalised as in the interests of animals because, it is claimed, they contribute to some aspect of disease control or animals’ physical health. This characterisation reflects a very limited and instrumental view of animal welfare, as well as ignoring other health problems that are inherent in common industry practices. Science, and I think the community generally, increasingly recognise that welfare is much more than the absence of disease or physical suffering but includes mental suffering and the necessity to provide animals with a good life, one that’s worth living. While governments and regulatory impact statements give lip service to these ideas, endorsed codes and standards reflect a very different view of animal welfare. All of these matters are amply illustrated by the process to develop poultry standards to replace the 2001 code of practice which I discuss in some detail in the book. This process began in 2015, public consultation closed in early 2018 yet in 2022 we still have no agreement on the final draft standards even though the reforms they contain are very modest. This process also illustrates another key characteristic of current animal welfare regulation: the interminable delay in effecting even minor reforms.

AASA: Other animals don’t fare much better, and the level of protection depends on the status humans confer to them. You use rabbits as an example: if you’re a rabbit your psychobiological necessities will naturally be the same whether you’re a free-living creature, a companion animal, a farmed individual or an experimental subject, but that’s not how the law sees you. For the law you are a pest, a pet, a type of food or fabric, or a model, and that’s going to reflect in how you can legally be treated?

EE: That’s right, it’s both anomalous and another glaring example of the mismatch between official rhetoric and the reality. Animal welfare laws are supposedly based on the longstanding recognition that animals are sentient but if an animal use or practice is considered ‘necessary’ very different rules apply. We’re not just talking agricultural practices here but all situations where human and nonhuman animals interact, even the regulation of companion animals which is heavily influenced by the interests of the pet industry. And because different laws apply in different settings we end up with a fragmented regulatory framework involving a variety of agencies. Some of these agencies lack relevant specialist expertise yet still have a crucial role in animal welfare, for example food safety regulators in abattoirs. This kind of fragmentation results in communication problems and a lack of accountability, all exacerbated by the lack of national uniformity in animal welfare regulation. For example, Victoria has recently toughened its companion animal regulation but breeders can just move across the border to NSW which has an abysmal record in this regard.

AASA: And if you’re a native, you may end up on the coat of arms and fluffed-up in souvenir shops but that’s not necessarily going to protect the real flesh-and-blood animals from anthropogenic violence. Kangaroos, for example, have been systematically persecuted in what is known as the largest commercial slaughter of land wildlife globally, their numbers have dropped so much that they may very soon join the list of other extinct species that Australia is famous for. An important drive of extinction is also habitat destruction. Is any of this regulated in any way?

EE: In the hierarchy of protection for animals living in the wild, native animals are above introduced species, with endangered native animals at the top. But the example of kangaroos clearly shows that being a native animal is no guarantee of protection when other interests are privileged, whether in the form of commercial hunting or damage mitigation. There are some laws, there are always some laws, but they assume the ‘necessity’ of the killing, they contain very weak and generally expressed protections, and their enforcement is wholly inadequate. Lack of enforcement is a major issue in all animal sectors but it’s particularly problematic in relation to killing that takes place in remote areas and/or when it’s dark. And, yes, habitat destruction is hugely significant for wild animal welfare, as well as the environment generally. Regulatory efforts, however, focus on controlling introduced species, including through the lawful use of methods that cause severe suffering, rather than addressing the human causes of biodiversity loss, such as land clearing. The impact of climate change is also tremendously important here but at best receives peripheral consideration in regulatory endeavours.

AASA: One can understand why industries based on animal exploitation may want to hide what goes on behind closed doors and in out-of-sight paddocks, but why is the Government, and politicians generally, on board? Do they know what they are condoning? And are we talking about the Commonwealth government or state/territory governments or both?

EE: We’re talking largely, though not exclusively, about state and territory governments but they know very well what they’re condoning. A major problem is that the government departments tasked with regulating animal welfare are typically agriculture and primary industries departments. These are the same departments that are required to promote the profitability of animal industries! As the administrators, and in some cases, the enforcers of the relevant laws, these departments are the gatekeepers of animal welfare yet their role is inherently conflicted. The same conflict occurs federally in those limited sectors where the Commonwealth has a legislative role, as is clearly illustrated by the very significant regulatory failures in live exports. Lawyers have been criticising this administrative arrangement for many years – even the mainstream Productivity Commission acknowledged that it’s problematic – yet politicians and regulators routinely deny any conflict of interest. Instead, administrators maintain they have a vested interest not a conflict of interest because, they say, efficient and profitable industries and animal welfare are complementary. Of course, this is nonsense not least because it assumes a very narrow and outdated understanding of animal welfare, one that contradicts contemporary science.

AASA: The official narrative also tries to make it sound as if it was only a small fraction of the population that is concerned with how animals are treated, a concern that is ‘extreme’, relevant only to some marginal groups of society. The current ‘regulatory’ arrangement and power relations have led to some bizarre but very concerning deviations of logic and ethics, such as the association of peaceful protesters and rescuers of suffering animals with terrorists! Clearly, most humans, not just some, want (and expect) other animals to be treated well, and I think most would expect much more information about their legal regulation to be readily available. The public may also be surprised to learn that Australia actually doesn’t rank high in animal protection on a global scale. But there are things that can be done quickly and easily that would help rectify the current legal and practical mess governing the lives and deaths of other animals in Australia.

EE: Yes, I think Australians would be surprised at our global animal protection ranking. And you’re right about the secrecy, not only in relation to our use of animals but the operation of the many agencies tasked with the regulation of their welfare. Whether it’s exhibited animals, those used for scientific research, farmed animals, those living in the wild or companion animals, it is difficult and time-consuming, and ultimately often impossible, to obtain detailed information about regulatory activities. This lack of transparency is completely at odds with government rhetoric but is perhaps unsurprising given the conflicting interests of government agencies under current regulatory arrangements. Even when there’s no direct conflict of interests, animal welfare is simply not a high priority for agencies whose principal objectives lie elsewhere – animal welfare is a secondary concern, just something tacked onto the department’s main responsibilities. This regulatory arrangement is not only detrimental to the administration and enforcement of existing laws, though this is bad enough, but also has a significant impact on opportunities for reform. Reviews of animal welfare legislation are underway at present in most of the states but they are overseen by the very same departments currently responsible for animal welfare and notorious for their conflicting interests – departments with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo! Researching this book confirmed for me that the current deficiencies in animal protection are systemic. Significant improvements in animal protection are unlikely until we have truly independent, properly resourced regulatory agencies, at state/territory and federal level, accountable to ministers with no conflicting responsibilities.

Essentially, there are two key reforms that we have to start now: one key reform relates to the need for transparency in animal use and regulation, the other key reform is the establishment of genuinely independent regulation. The newly elected Labor government has a great opportunity to show leadership and begin rectifying the situation at a federal level. Without delay the same reforms should begin at state/territory level. I feel strongly that this is where we need to focus our energies for legal change.

[1] Reported in Nonhuman Rights Project Inc, on behalf of Hercules and Leo v Stanley (152736/29 July 2015) 32.

Elizabeth Ellis is an honorary senior fellow with the School of Law at the University of Wollongong where she taught for many years. She introduced animal law into the Bachelor of Law degree in 2008, making UOW one of the earliest Australian universities to teach the subject.

Teya Brooks Pribac, PhD, is an independent scholar and multidisciplinary artist, living in the Australian Blue Mountains with other animals. Her recent publications include the award winning monograph Enter the Animal, and the recipe collection Not Just Another Vegan Cookbook.