Zhuangzi and Huizi were strolling along the bridge over the Hao River. Zhuangzi said, “The minnows swim about so freely, following the openings wherever they take them. Such is the happiness of fish.” Huizi said, “You are not a fish, so whence do you know the happiness of fish?” Zhuangzi said, “You are not I, so whence do you know I don’t know the happiness of fish?”

– Zhuangzi: Essential Writings, translated by B. Zyporyn

Jonathan Balcombe is a biologist, ethologist, animal advocate and author. In 2016 he published a book on fishes, What a Fish Knows, which has since become a bestseller and been translated into thirteen languages.

As we learn from the book, a fish knows and feels a lot of things. Fortunately, we can talk about this today but that hasn’t always been the case. For instance, in 1992 a scholar published a warning in the journal Science stating that studying nonhuman animals’ consciousness wasn’t something she’d recommend to anyone without tenure. Close to ten years earlier the American ethologist Donald Griffin’s book Animal Thinking was described as The Satanic Verses of Animal Behaviour.

In that period you were a student of biology and ethology. What was it like?

JB: There were certainly strong opinions about animals and their inner lives. I’m happy to say that science has been emerging from that past agnosticism, that past reluctance to ask questions about what animals think and feel, and sometimes even a hostile reluctance as you’ve just described in your question. Now it’s no longer taboo, it’s de rigueur to study animal emotions and animal cognition. There’s a journal called Animal Cognition, for instance, and we have Animal Sentience. This is a sign that these subjects have taken on scientific acceptability, and scientists are now asking good and interesting questions about other animals and their lives. So I think we’ve moved forward a great deal in the past few decades. We’re still waiting for the science that shows that animals experience their lives to translate into changes of behaviour: what people eat, for instance, industrial fishing and factory farming and all those atrocities that are still going on as we speak, but if we’re going to get there I guess we have to go through this step first, and that’s happening.

By the end of the 1990s there was substantial interest in nonhuman animals’ cognition, and in the following decade their emotions started to receive considerable attention, too. What made the change possible?

JB: I’d like to touch on some historical figures: Charles Darwin made the change possible, it was 150 years ago but his ideas helped to connect us biologically to all other animals. This, I think, was a critical early step in bringing us to where we are now. Then you mentioned Donald Griffin: he helped us start asking how animals think and feel, and the whole cognitive ethology revolution is partly attributable to him. Those two people I like to cite as really important figures. To this we should add the philosophy of animal rights: the philosophy or just the idea that we should protect animals on principle not just because it’s a nice thing to do. Peter Singer and Tom Regan are two important philosophers of the latter half of the 20th century who did a great deal to bring us into the current era. Again, I want to reiterate, I’m not saying that we’ve arrived yet, we have a long way to go, it’s in many ways worse than ever, but we are thinking about these things, beginning to act on them in a way that we’ve never done before. The unprecedented numbers of vegetarians and vegans in the world: the numbers are growing far too slowly for the likes of you and me to be happy about it but they are growing.

If we return to your student years briefly, did anyone try to suppress you? Your tutors, for instance, instructing you not to discuss animal consciousness or similar?

JB: No, I’m happy to say that never happened to me. I did become an activist when I was an undergraduate student. I remember going to meet my entomology professor and saying I didn’t want to snip off the head of my locust, I wanted to anaesthetise the locust first. He let me put the locust in ether and knock the locust out. To this day I don’t know if that was a better method but at the time I felt like it was.

I was never actively suppressed. However, there were forces at work that reinforced the dominant paradigm of humans above all other animals, such as when we were given a test on frog anatomy. Each of us was given a freshly killed frog – mine was a pregnant female with tonnes of eggs in her body – and I thought what a waste of that frog’s life just so they can test my knowledge of anatomy that could have been tested in many other ways. Or in the genetics lab: all the fruit flies were going to the morgue; I actually released them onto my desk and let them fly off when they recovered from the ether. In another genetics lab the instructor took a pair of scissors and started snipping off all the legs and the wings of a large live locust – just callous! One may debate whether insects feel pain but let’s assume they can and treat them accordingly. Those kinds of experiences were negative for me and they didn’t suppress my desire to change how we view other animals but who knows what kind of corrosive effect they may have had on less sensitive students.

As a scientist and advocate you stress the importance of positive sentience. Your initial motivation for this was to dispel the myth of “nature being red in tooth and claw”, a constant battle for survival. There’s more to nonhuman animals’ lives, isn’t there?

JB: Yes, that was the beginning of my writing popular science books: Pleasurable Kingdom, which I began writing way back in 2003. That book was a very exciting project for me because I realised “wow! we really have been neglecting the pleasurable side of animals’ existence!” We recognise it as critical to our own wellbeing and quality of life. We have those expressions: quality of life, wellbeing etc., and yet we’ve been pretty dismissive about its significance to other animals. Why would we think it’s any different for them in terms of not just avoiding pain but seeking and enjoying pleasures? There’s a good adaptive Darwinian basis for the importance of pleasure that acts as a motivator, and award systems are very well studied. But they were never really couched in the sense of an animal’s experience and the adaptive benefits of having it. I’m pleased to see that there’s more attention to pleasure now. I think it would have been inevitable because there’s more attention to animal sentience and consciousness and this is part of the discourse. I think it’s very important that we step back and look at animals’ lives as not just avoiding pain – that’s only half of the piece – there’s this whole other piece, which is seeking rewards, be it food, comfort, companionship, sex. It all fits, it all makes sense. And if we see animals that way we realise they have a lot to lose by being confined and ultimately killed. We take away their opportunities for pleasure.

On a parallel note, in animal rights advocacy generally, substantial effort goes into showing the extent of animals’ physical suffering. The suffering is immense and it’s of course important to make the public aware of it. Do you think we should be focussing more on positive sentience? On presenting a more integrated view of the nonhuman persons and their communities, of other nations as Beston calls them?

JB: I think a balance is good, I think we should pay attention to all of those things: pain, suffering, pleasure, enjoyment, etc. I like what Tom Regan the philosopher said: in social movements we need to have many different kinds of hands on many oars to row the boat forward because not everybody wants to go through the same door. Most people, let’s face it, are not ready to go vegan, maybe not even vegetarian, but they may be ready to go meatless Monday. Is meatless Monday enough? No, of course not, but it’s a start, and it may get them on the right track. We need to have a lot of doors available to people, we need a lot of diversity in the movement. I think it’s important we have animal rights groups but it’s also important we have humane societies, and hopefully everybody is keeping their eye on the prize, i.e. moving towards abolition ultimately. We need to have a fundamental change, which will be better for us as well as other animals.

What a Fish Knows was a big project. What inspired you to start research on fishes?

JB: I knew there was a lot of neat science about them, and I knew also that there was a lot of public ignorance about them – not wilful ignorance necessarily, but people simply don’t know. So those two ingredients are really key for a worthwhile project, in this case a book. The fact that there’s great science, and the fact that there’s a great amount of public misunderstanding and misinformation are the main reasons I wanted to do it, and no one else had done a recent book on fishes that I was aware of.

Fish(es) constitute an extremely varied group of animals that, separately and jointly, possess capacities comparable to those of mammals and birds. For instance, we may not think of fishes as caring parents or faithful lovers, but both extended parental care and pair bonding have been observed in fishes. What other amazing things can fishes do? Can they use tools?

JB: Yes, they can. They have limited options for tool use because they don’t have hands like ours, but they have a mouth and they have a good brain. They can use those as well as physical coordination to manipulate other objects in a tool-like fashion.

Do they learn from others?

JB: Absolutely. Observation learning is one way they learn from others. I don’t know if there’s any specific example of actual teaching but certainly some more passive learning where they look and they see what others do and they learn from that.

Some talk about culture in fishes. What is fish culture?

JB: Biologists define culture as essentially any kind of trait that is not heritable, that is not genetically transferred from one generation to another, but that nevertheless gets behaviourally transferred. That’s a cultural trait. And yes, that has been scientifically documented in fishes, such as nest sites by cichlid fish. They have particular nest site preferences that are idiosyncratic to the individuals and they are not based on any particular biological feature, it’s just an internal preference that they have.

Is their memory really as bad as some humans think?

JB: Of course not. The old myth about the three-second goldfish memory is complete nonsense, and as a number of studies shows, even the smallest little fish – maybe we shouldn’t get into size-ism, it doesn’t really matter how big or small they are – can remember things a year after they learnt it. And there are some memory skills by some fish that are superior to our own memory, memory skills such as forming mental maps.

Last year the cleaner wrasse passed the mirror self-recognition test. Why is this important?

JB: Passing the MSR test is considered the gold standard for self-awareness in nonhumans. It’s very significant because self-awareness is considered to be a very high level cognitive characteristic in a creature. Of course, you have nay-sayers who will then say “well if fish passed it then it can’t be that sophisticated” instead of “a fish passed it so that means that the fish is very sophisticated”. I prefer the latter interpretation but whichever way you slice it they passed it and it was a rigorous test, it was properly designed, and we should take notice from that. It’s just another proverbial feather in the cap of fishes that showed how sophisticated they are, that they have mental lives and that they are aware of themselves, or at least the cleaner wrasse is.

And of course fishes exhibit a full array of emotions, including complex emotions such as trust and loyalty (e.g. relations between cleaning and client fishes) but also depression. Can you talk a little bit about emotion in fishes?

JB: Definitely depression and pain are very well studied, and well demonstrated in fishes. Farmed salmon, for instance: many stop feeding, they become listless, and they die; the scientists measured their cortisol level and the stress hormone was exceedingly high. All of this is consistent with what we’d expect of a depressed animal. There’s anecdotal evidence of grief, too. In goldfish, for example, if one dies, the other shows signs of grief if they were attached: they stop eating and don’t do very well. Getting along in goldfish is not a given, a goldfish doesn’t just get along with any goldfish. There’s a lot of anecdotes of grief. This is not rigorous science but it’s the kind of evidence that may lead to scientific studies of the phenomenon, and fish show characteristics both emotionally and behaviourally that would predict that they definitely can feel grief, that they can feel attachment.

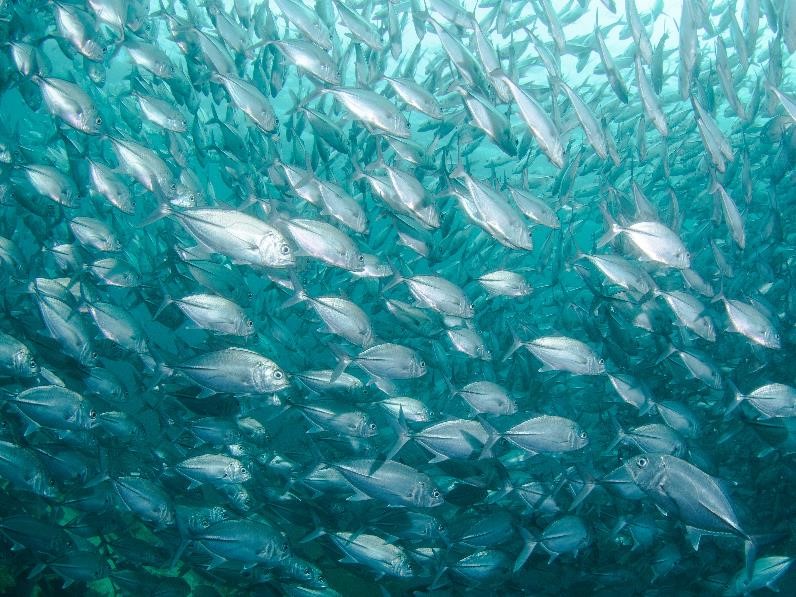

People don’t normally associate the term factory farming with fishes. Yet we have large underwater factory farms that mimic the oppressive factory systems on land. So high is the number of piscine individuals we kill that we don’t even count them, we measure their death in tonnes instead. How do fishes live and die for human appetite?

JB: Agriculture and fish farming operations are factory-farm-like. They completely qualify in terms of crowding, intensive confinement, the prevention of natural behaviours, the stresses and strains of the crowding, competition for food, parasite loads, pesticides, and just the chronic deprivation of not being able to do what you would normally want to do: not being able to move where or when you want, not being able to get away from the waste and the stress, the crowds. It’s just stressful for them on multiple levels. Add to this how they are treated: I have served as an expert witness on undercover investigations of aquaculture operations and what I’ve seen shows not necessarily deliberately cruel behaviour though I have seen that too, but just an indifference. It’s a business. For example: when they move the fishes from one place to another large numbers are funnelled into one pool from another, the water is bubbly, you often see fishes on their sides gasping, dying, or dead. Some of them are just dumped onto the ground. It’s a predictable level of abuse on so many levels. It’s terrible the way they are treated, and the public doesn’t know. They think aquaculture sounds nice: “oh what a lovely, clean way of producing fish”. Another problem with aquaculture is that it doesn’t relieve the pressure on wild fish populations because most of the fish people like to eat are predatory fish and they are fed other wild-caught fish like herring and menhaden.

This brings us to the next question: the environmental implications of eating fishes, captive or free-living.

JB: Fishes are the only animals that we eat in huge amounts that are wild-caught. Both wild-caught and farming practices are ecologically extremely troublesome, not just for fish. In the case of commercial fishing at sea, a huge number of seabirds, almost all the albatross species – about 22 species – are in danger of getting caught on fish hooks and there’s a very high mortality. There have been some improvements but it’s still a very big problem. Marine mammals and others, e.g. sea turtles, of course get caught in nets all the time, so it’s not just the fish themselves that are getting harmed by these operations. With fish farming, I already mentioned the catching and feeding of wild fish in farms, but there’s also the problem of pollution: all the concentrated waste and chemicals and pesticides from these farms gets through the nets and is washed out to sea, contaminating wild ecosystems.

Also, if the ocean ecosystem collapses we would be in big trouble. We rely on the ocean for oxygen: more than half of the world’s supply of oxygen comes from water, it comes from oceans. I don’t think we’d survive that. They are saying that at the current rate we could lose all fish by 2050. We need to realise that that would really harm us as well, really endanger us, we can’t keep going like this, we have to change our approach, and we’re not really doing it yet.

Do you have a favourite fish species? (If yes) What’s so special about them?

JB: I wouldn’t know where to start. There are so many. I think they’re all just wonderful. I snorkel a lot and I just love watching them and never get tired of it. If I try to give one example – it wouldn’t be my favourite, it would just be one of the many that I adore – the leaping characin. The name comes from their unusual reproductive behaviour: it’s almost as if they have sex in the air. They leap up and then they combine in mid-air, they grab onto a leaf for a second and leave their eggs and sperm on the leaf before dropping back into the water. They do that repeatedly with incredible time coordination: they have to jump at the same time, you can see online videos of this activity . To add an element of virtue to the behaviour, for several days thereafter the male spends all his time under the nest splashing water up with his tail to keep the eggs wet. It makes you wonder why go to all that trouble but apparently they are safer from predators above the water than below the water.

Thank you, Dr Balcombe

Interview prepared by Teya Brooks Pribac; transcribed/edited from a spoken interview

Photo credits: Author: author’s archive; Fish: David Clode and Jean Wimmerlin at Unsplash